When the Prosecutor Picks the Man

We were warned about a prosecutor--or president--who might "pick people that he thinks he should get, rather than pick cases that need to be prosecuted."

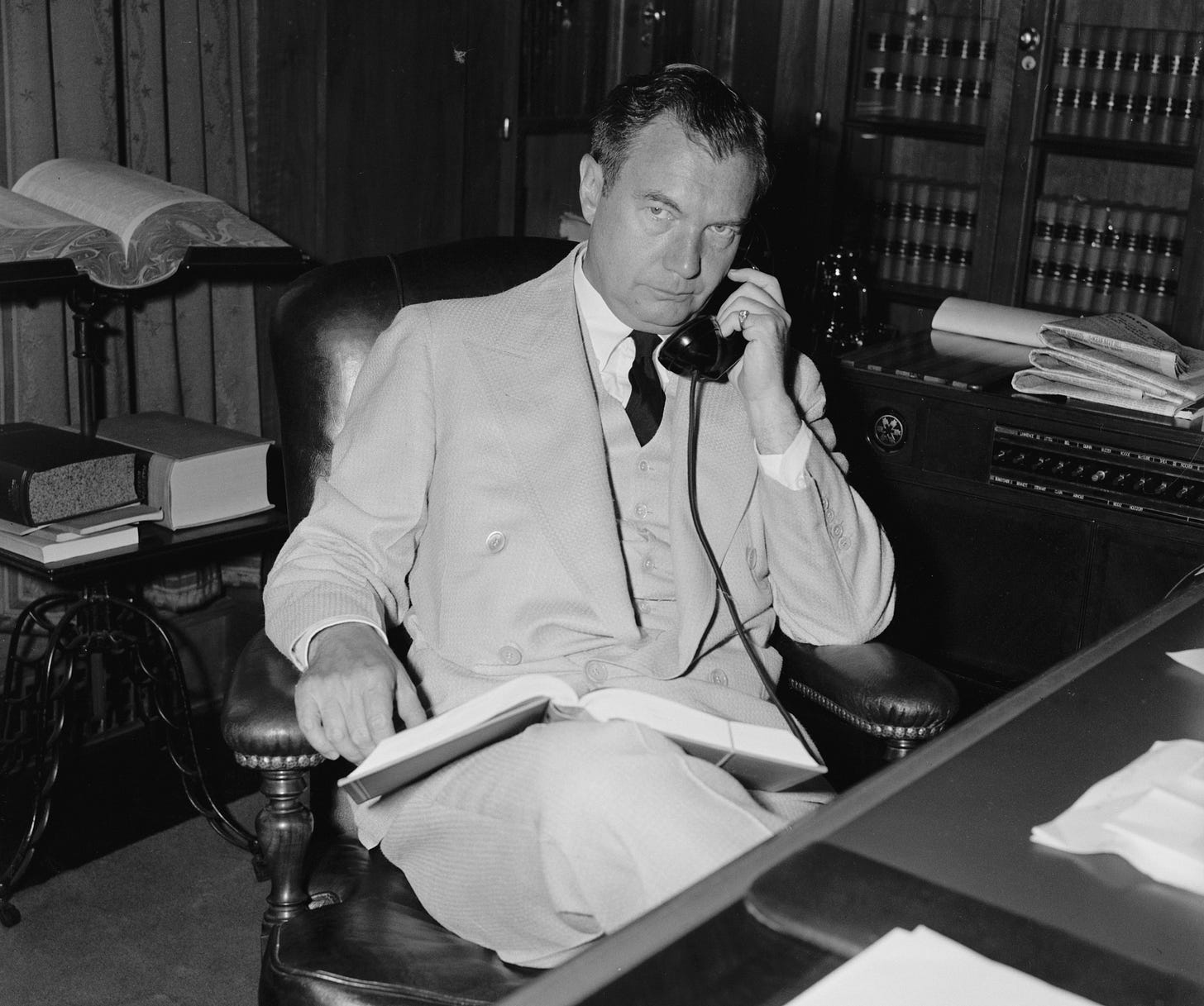

On April 1, 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s attorney general, Robert H. Jackson, addressed the Second Annual Conference of U.S. Attorneys in Washington, D.C.

His speech, “The Federal Prosecutor,” is remembered as one of the clearest statements ever made about the dangers of prosecutorial abuse, and it remains widely quoted in American legal circles. Roosevelt appointed Jackson to the Supreme Court the year after this famous speech, and Jackson later served as Chief U.S. Prosecutor at Nuremberg.

Jackson warned that the greatest threat to liberty was not just crime itself but the misuse of the prosecutor’s power—especially when political leaders demand that prosecutors target individuals rather than crimes.

The “most dangerous power of the prosecutor,” Jackson said in his address to U.S. attorneys, is “that he will pick people that he thinks he should get, rather than pick cases that need to be prosecuted.”

I urge you to read the full text of Jackson’s speech here (perhaps before some MAGA flunky removes it from the Department of Justice’s website).

Below I’ve included some of the most quoted lines, words that resonate powerfully on this day when we are becoming the country Jackson warned about—a place where “law enforcement becomes personal, and the real crime becomes that of being unpopular with the predominant or governing group, being attached to the wrong political views, or being personally obnoxious to or in the way of the prosecutor himself.”

On the prosecutor’s power:

The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America.

His discretion is tremendous. He can have citizens investigated and, if he is that kind of person, he can have this done to the tune of public statements and veiled or unveiled intimations. Or the prosecutor may choose a more subtle course and simply have a citizen’s friends interviewed. The prosecutor can order arrests, present cases to the grand jury in secret session, and on the basis of his one-sided presentation of the facts, can cause the citizen to be indicted and held for trial. He may dismiss the case before trial, in which case the defense never has a chance to be heard. Or he may go on with a public trial. If he obtains a conviction, the prosecutor can still make recommendations as to sentence, as to whether the prisoner should get probation or a suspended sentence, and after he is put away, as to whether he is a fit subject for parole.

While the prosecutor at his best is one of the most beneficent forces in our society, when he acts from malice or other base motives, he is one of the worst.

On “the most dangerous power”:

What every prosecutor is practically required to do is to select the cases for prosecution and to select those in which the offense is the most flagrant, the public harm the greatest, and the proof the most certain.

If the prosecutor is obliged to choose his cases, it follows that he can choose his defendants. Therein is the most dangerous power of the prosecutor: that he will pick people that he thinks he should get, rather than pick cases that need to be prosecuted.

With the law books filled with a great assortment of crimes, a prosecutor stands a fair chance of finding at least a technical violation of some act on the part of almost anyone. In such a case, it is not a question of discovering the commission of a crime and then looking for the man who has committed it, it is a question of picking the man and then searching the law books, or putting investigators to work, to pin some offense on him.

On the danger of targeting the unpopular:

It is in this realm, in which the prosecutor picks some person whom he dislikes or desires to embarrass, or selects some group of unpopular persons and then looks for an offense, that the greatest danger of abuse of prosecuting power lies. It is here that law enforcement becomes personal, and the real crime becomes that of being unpopular with the predominant or governing group, being attached to the wrong political views, or being personally obnoxious to or in the way of the prosecutor himself.

In times of fear or hysteria, political, racial, religious, social, and economic groups, often from the best of motives, cry for the scalps of individuals or groups because they do not like their views.

Particularly do we need to be dispassionate and courageous in those cases which deal with so-called “subversive activities.” They are dangerous to civil liberty because the prosecutor has no definite standards to determine what constitutes a “subversive activity,” such as we have for murder or larceny. Activities which seem benevolent and helpful to wage earners, persons on relief, or those who are disadvantaged in the struggle for existence may be regarded as “subversive” by those whose property interests might be burdened or affected thereby.

Those who are in office are apt to regard as “subversive” the activities of any of those who would bring about a change of administration. Some of our soundest constitutional doctrines were once punished as subversive. We must not forget that it was not so long ago that both the term “Republican” and the term “Democrat” were epithets with sinister meaning to denote persons of radical tendencies that were “subversive” of the order of things then dominant.

On what makes a good prosecutor:

The qualities of a good prosecutor are as elusive and as impossible to define as those which mark a gentleman. And those who need to be told would not understand it anyway. A sensitiveness to fair play and sportsmanship is perhaps the best protection against the abuse of power, and the citizen’s safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth and not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes, and who approaches his task with humility.

Lindsey Halligan, the new DOJ prosecutor in the Comey case is in way over her head. It will show at the trial, if the matter ever gets that far. This assault on decency, the rule of law, and Justice Robert Jackson's description of what being a good prosecutor is all about, will fail. Trump will be furious. He will insist on other assaults. He will lose. I'm hoping that juries will take a page from the Washington, D.C. grand juries who refused to indict cases brought by the DOJ during "the troubles" in that city. We can wear this motherfucker down. Case by case, protest by protest, boycott by boycott, written word by written word, podcast by podcast. And we will win because there are more of us than there are of the regime and all of MAGA. And Trump knows it and that is why he is losing it more and more, every day. I'm not sure how long he can last, with his health and head in steady decline. Let us keep that in mind as we fight to save our country from the traitors.

AG Jackson certainly told us who would be a good prosecutor. It’s a shame that our Dear Leader is unable to find a good prosecutor, and therefore puts his thumb on the scale by appointing others who should never have been graduated from law school. Thank you, Ryan, for this post.